Torment - Tides of Numenera

(Here be Spoilers)

Almost two years ago, just after finishing Pillars of Eternity (and its XP-less combat system) for the first time, I remember myself musing over the necessity of combat in cRPGs. For a long time I’ve considered combat to be one of the four main pillars of the genre, along with exploration, story, and character development. Pillars, by removing the XP reward factor (though not the treasure one) from the equation, gave us a glimpse of how one of these four pillars could be diminished without any impact on the whole structure’s stability. Torment: Tides of Numenera (T:TON from now on), the spiritual successor of 1999’s mythic Planescape Torment, takes a grand leap towards this direction, presenting us with a minimal amount of mandatory battles.

Let’s get some things out of the way: The game’s graphics are masterfully designed and materialised, full of wonder and a semi-scifi, semi-exotic-fantasy look. The Mere’s screen paintings are gorgeous. Those into isometric cRPGs will adore T:TON’s visual part, and at the end of the day this is what really matters, for this a game for them(us). The same goes for music amd sound, which nicely and very discreetly frame the environment. Voice acting is scarce, a thing about which I couldn’t care less.

One of the Mere screens. The Meres are an innovative idea (perhaps implemented somewhat hastily), which are underlined by the question: If you had the power to alter another being’s life course without permission or knowledge, would you do it?

One of the Mere screens. The Meres are an innovative idea (perhaps implemented somewhat hastily), which are underlined by the question: If you had the power to alter another being’s life course without permission or knowledge, would you do it?

Concerning combat: It is easily avoided in most cases. The inclusion of combat in the super-category of Crisis tones down the former’s importance – it seems that RPGs can do away with it, though their image afterwards may well be different from what we now have in mind as virtual RPGs. Crises are situations which can be resolved by force, but also in one or several other ways. In general they require a bit of thinking, them being organized more as riddles and less as clickfests or optimization/micromanagement challenges (i.e. see the adventuresque Sticha lair). Each one is more or less carefully designed, far away from a random-encounter logic.

A brief look on some things that bothered me:

-There are secret timers on a few quests, which timers are tied to the party rest count (this could be considered an asset for a lot of people, and it does make the game world more realistic – though there is a journal bug for failed quests of this type).

-Its short duration (T:TON took me roughly 31 hours to finish on the first playthrough, without any walkthrough, and completing all the quests I could find. Several of the areas are underdeveloped, especially on the later half of the game – the Maze being one of them).

-Not being able to return to previous areas and deal with any unfinished quests.

-Several minor bugs.

-A game engine thing: when the camera is at a place of an area far from your party (and the PCs do not appear on the camera) and you click so as it starts moving towards this area, the camera forcibly resets back to the party.

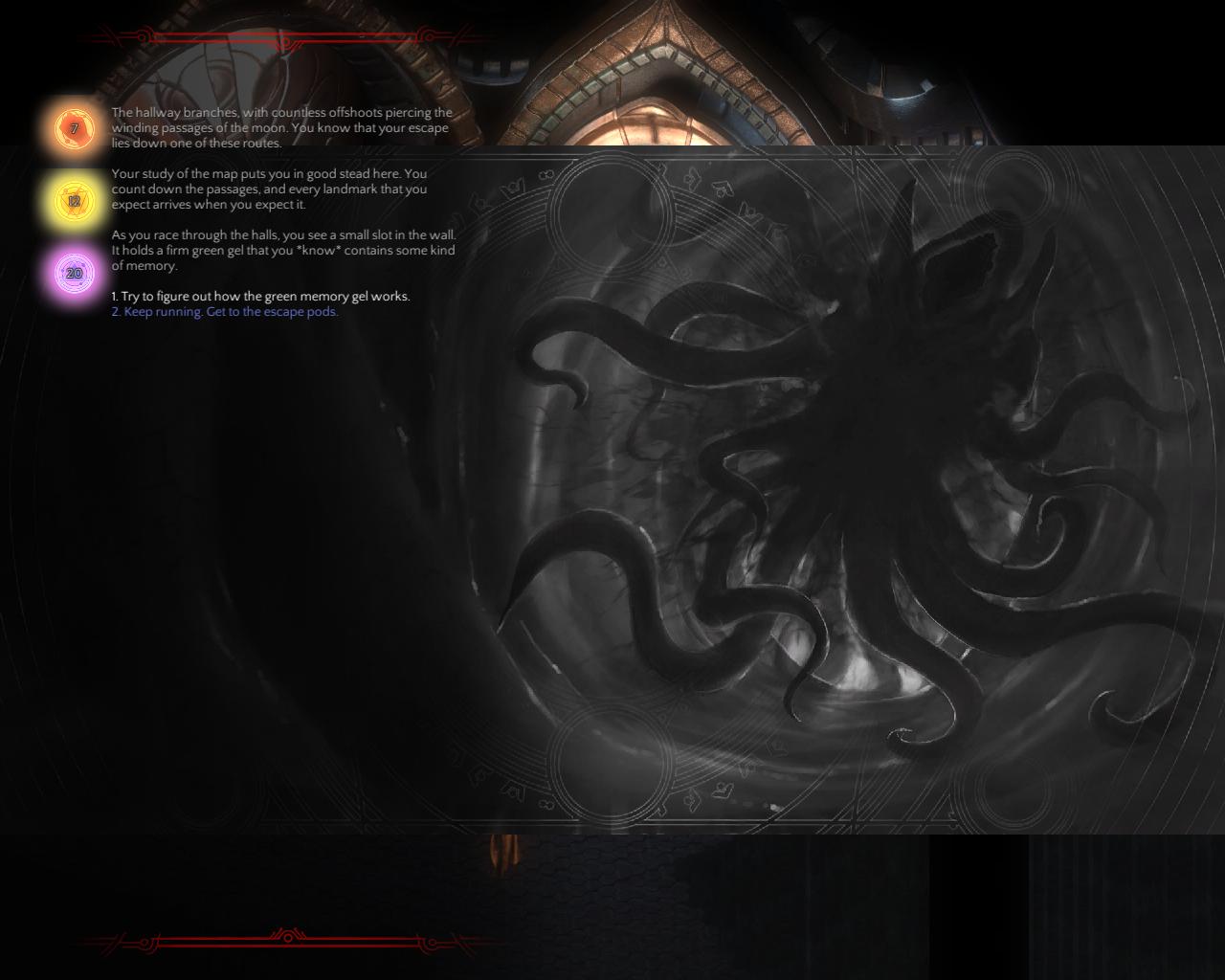

One of the Bloom’s Maws, a definite homage to Sigil’s portals

One of the Bloom’s Maws, a definite homage to Sigil’s portals

Moving on to the juiciest aspects of the game, I must stress here that T:TON is not a game for people who do not like reading (in games or otherwise). There are many thousand dialogue lines in here, with the word count reaching a whopping 800.000. If at some point you feel that you cannot read more, then don’t; better save and quit til your mind is clear (speaking from personal experience I wasted several conversations this way – on the bright side, more things to read on the second playthrough). Reading is the single most important player activity in T:TON – if you remove the dialogues from the game you’ll be left with a grotesque monstrosity, an incoherent collection of lovely graphics and slightly underdeveloped mechanics.

Protagonist-wise the story has a definite Gnostic hue. The whole Changing God and Castoffs plot is a catalyst for questions you may already have asked and dilemmas you may have faced if you ever had a brush with the occult idea of humans being the cells or experience accumulators or sensory organs of the Divine. In what ways can one’s individuality and the value of it be compared with that of a greater whole? Can a cell rebel against the organism it is part of? Is the modern human able to change his perception focus from the scale of person to another grander or more diminutive scale? There is much food for thought and contemplation in here, theological-, occult-, and social-wise.

Still, T:TON’s story is less about the protagonist (and this is why I can accept the almost complete absence of character creation cosmetic options – you only select the gender), and more about fragments of other characters’ (NPCs’) stories. The game is a Sensate’s (I could not resist including an obvious reference to my favourite Planescape faction) paradise, with tidbits all around to taste and immerse yourself in. It is like being thrown in the midst of an immensely varied banquet of lives and experiences, which you can sample. One could say that the Protagonist/Player is an Interface; this actually leads to the interesting thought that this may be what a being a god feels like – being an interface for a multitude of lives, fragments of which stay and are lived through you. A few such stories that particularly impressed and will stay with me are those concerning:

-A man who apprentices his young self.

-A special kind of adoption, in which the foster parents adopt children born centuries ago, reaching the current era through time portals.

-A vehicle that crashed years ago, the guilt-ridden AI of which keeps alive the memory of the passengers that died in the crash by projecting holograms of them.

-Rhin.

Sagus Cliffs, a city that will probably stay with me in almost the same way Sigil did

Sagus Cliffs, a city that will probably stay with me in almost the same way Sigil did

As in the original Torment, Numenera is characterized by the absence of an area with the essence of “home-base” throughout the game. Sagus cliffs serve as a sort of home town (or rather as the Only town, as Sigil was in PT’s first chapters, since the whole of the first part takes place in it (starting area aside)) but after leaving it there is no going back. This is true for almost all areas (apart from the Maze) – they are like beads on a string: once you pass one you cannot return. The Maze is a kind of home, you can visit it somewhat voluntarily, but it is not a place you can share with your companions (thus camaraderie is lost), and it also is never completely safe in the sense of the explored, mapped, and devoid of menace. This linear approach, akin to that of a strict narrative, deprives you of experiencing a place a-temporally, of having a city as home – for home is strongly characterized by its always being there, of being able to return to it, of never abandoning you, despite what you do. It would be nice to be able to see the consequences of your actions shaping a place, and not just see some old faces appear in new spaces.

In the end T:TON is a sprawling modular interactive narrative, a rough glimpse towards a possibility of what a combat-less cRPG could look like. I say rough because non-combat challenges could definitely be more challenging and not just depended on trivialized character skill checks; more challenge for the player (and not the characters) would be welcome. Where T:TON really shines is not in the framework but in the content department. This is a game to make you dream about its world and denizens, an artistic creation whose stories you may revisit in reveries, an entity that sows delicious seeds. A journey which may bring tears in your eyes and goosebumps on your skin, just as Planescape Torment did. From this point of view, Numenera is a worthy successor to what is one the most acclaimed RPGs of all times – though it would be best to let it carve a place of its own.